When I started writing javascript in earnest a couple of years ago, I was stuck in a very procedural way of thinking — all of my functions executed synchronously. If you replaced function with def and removed all var keywords, you would be reading Ruby (true story: yesterday I was debugging an issue with a React module and put in a binding.pry instead of debugger :facepalm: Old habits die hard).

Last year, I joined a team that writes javascript in the Node.js style, using callbacks for flow control. While I became familiar with the pattern pretty quickly, the whys and wherefores were missing from my understanding. Today I am filling in the gaps by reading Node.js Design Patterns by Mario Casciaro and Luciano Mammino.

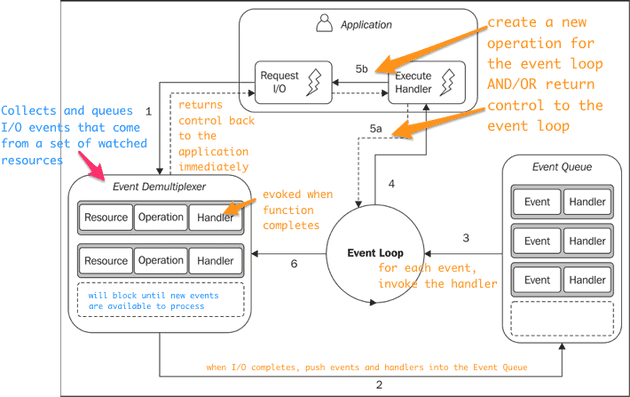

The Event Loop

The first step to understanding asynchronous javascript is to understand the event loop. It is a single thread that processes one message at a time, as they appear in the FIFO event queue.

image credit: Mario Casciaro and Luciano Mammino from Node.js Design Patterns. Colour notations are mine.

- An I/O request is sent to the event demultiplexer.

- The event demultiplexer queues the I/O instructions along with the context and a callback function that contains the instructions for what do to with the result once it is received.

- When the I/O order is filled, the event demultiplexer pops an event on to the event queue, with the filled I/O request, and the callback handler.

- The event loop pulls the event off of the event queue and applies the result to the callback function.

- The event loop either sends the result of the callback operation to the application, or generates more I/O work for the event demultiplexer.

When I check my email in the morning, I go through a similar process:

- My inbox is the event demultiplexer, where requests for resources are made.

- I (as the event loop) process emails from in the queue from oldest to newest, and I only process one at at time.

-

For each message I read the context and perform one of two actions (callback):

- Process the message and return to the queue to pick up another message.

- Add a new action to my todo list event queue along with the a reminder to attach the result of the new action to the email when I respond (callback).

When I am finished with my email inbox I start on my todo list, performing the actions required and responding to the email. Sometimes the action will generate additional actions, which I append to the end of my todo list. While the idea of an infinite todo list is a little disheartening to a human, this is how the V8 javascript engine was designed: it performs the work with maximum efficiency, and can do so with only a single thread.

The difference between synchronous and asynchronous javascript

Synchronous javascript can be easily identified by the use of a return statement, which returns control back to the caller.

function introduction (firstName, lastName) {

return 'Hello, my name is ' + firstName + ' ' + lastName

}

introduction('Keighty', 'Leonard')

// "hello! my name is Keighty Leonard"Asynchronous javascript uses a ‘continuous passing pattern’, where the result of a function is passed to a handler for further processing.

function createEmailAddress (firstName, lastName, callback) {

// create asynchronous call

console.log('before the async')

setTimeout(function () {

// do some work

var email = firstName.toLowerCase() + '.' + lastName.toLowerCase() + '@example.com'

console.log('during the async')

// pass the result of the work to the callback

callback(email)

}, 2000)

console.log('after the async')

}

var cb = function (result) {

console.log(result)

}

createEmailAddress('Keighty', 'Leonard', cb)

// > before the async

// > after the async

// > during the async

// > keighty.leonard@example.comcreateEmailAddress is called. When execution reaches the setTimeout function, and the 2000ms have elapsed, the callback passed to setTimeout is placed in the event queue, awaiting its turn for execution. The thread is release and does not have to wait for the setTimeout period to elapse before continuing execution — it continues with the second console statement (‘after the async’). When the setTimeout callback is finally processed, the firstName and lastName variables are still accessible because they exist in the function closure.

Javascript has many features that make the continuous passing pattern easy:

- Closures allow you to access the environment on which a function was created, no matter when the callback is invoked.

- Functions are first class data types, meaning they can be assigned to variables, passed as parameters, and stored in data structures.

More on the event loop and event-emitter observer pattern to come!